The Bitter Taste of Sugarcane

Reporting by János Chialá and Vinith Xavier.

Southern India, 2016.

Farmers have been working the lands of southern India for more than 10,000 years, making wise use of its fertile soil and abundant rains. To a visitor from less tropical places, the Mandya district in the state of Karnataka appears as an expanse of lush, tilled plains where the sugarcane fields stretch as far as the eye can see.

Mohandas K Gandhi, one of the founders of independent India, placed the humble Indian farmers at the centre of his vision for independence. In his 1909 book about Hind Swaraj (Indian Home Rule) he argued that they had “managed with the same kind of plough as existed thousands of years ago” and that rural India remained untouched by the corruptions of modernity: “The common people lived independently and followed their agricultural occupation. They enjoyed true Home Rule.”

But once independence was achieved, the new Indian government embraced the Green Revolution to the feed its growing population and join the developed world, introducing modern technologies, chemical fertilizers and pesticides to its agriculture. Then, in the 1990s, the country embarked on a series of neoliberal economic reforms, deregulating the markets and opening them up to international trade. Free from foreign domination and working in a modern, developing country, it seemed as if the farmers of India could finally work for themselves and enjoy the fruits of their labour.

Yet, millions of Indian farmers barely make a living, and many think they don’t even have a chance of doing that, choosing to end their lives in what has become one of the greatest waves of mass suicides in human history: hundreds of thousands of Indian farmers have committed suicide in the last three decades.

In the southern state of Karnataka, almost 1,000 farmers killed themselves in 2015, with about 90 cases among the sugarcane farmers of the Mandya district alone, and while the data for 2016 is still unpublished, some 200 suicides were already being reported by the month of July. There is no single motive behind this wave, yet there are several common elements. Growing amounts of personal debt is one of them.

Alongside countless other farmers throughout India, sugarcane growers are struggling to earn enough to survive, and are forced to borrow money to continue farming. And they are not alone in this crisis which also affects widows, entire families and fellow farmers, most of whom readily admit that they also fell in the cycle of debt. “It’s part of being a sugarcane grower”, they say.

Sugarcane was once one of the most profitable crops, they also explain. But things have changed.

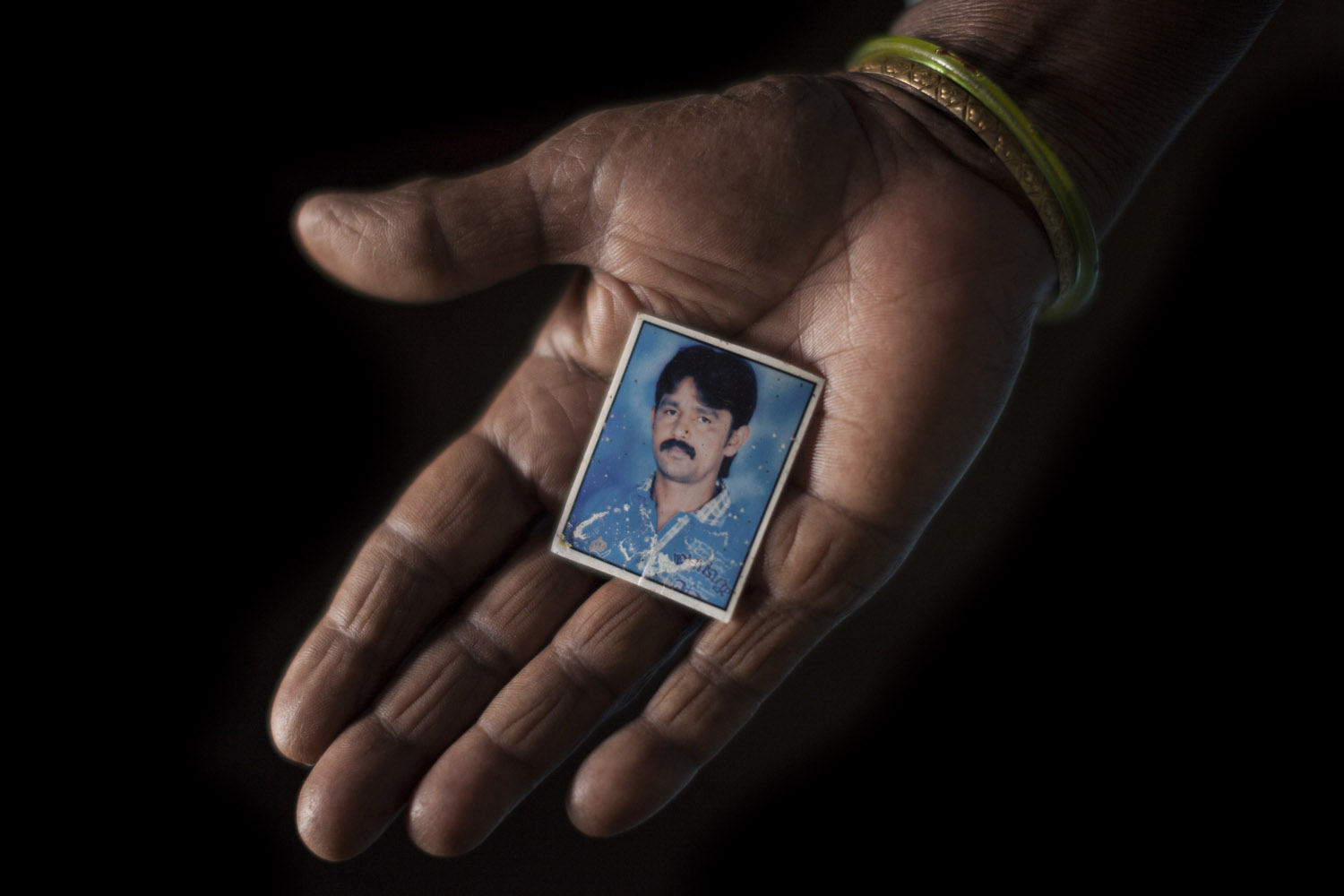

Shivanna Kempegowda was a 36-year-old sugarcane farmer from the village of Sadolalu, a few kilometers from Mandya. He was the sole breadwinner in his family, and seven other people depended on his income: his parents, his wife who suffered from thyroid problems, his two children and his sick brother along with his wife.

No one suspected that he was facing difficulties with debt. But on one day in July 2015, after dropping off his son at school, he drove into town and bought a bottle of alcohol and some pesticide.

After lunch, he went off to his fields as usual. At 5pm in the afternoon he called his niece, telling her that he had drunk the pesticide and that he wanted to see her one last time. The whole family rushed to the field but they were too late. By the time they arrived and took him to the hospital, he had already passed away.

Shivanna was heavily in debt. His debts amounted to six lakhs (about $8,500) and he was feeling desperate with the burden. Even if he had managed not to borrow more money to run the farm, it would have taken him six entire harvests just to break even with the five acres of land he owned and leased and his average profit of 20,000 rupees ($295) per acre.

“He would not share his troubles with anyone,” Shivanna’s mother Savithriamma says. He was known to be a responsible person who didn’t drink and “was very happy that his second child was a girl. He did all the work, took her to the temple, the astrologer, everything,” she says. “That’s why he bought the liquor, to bring himself to do what he did.”

The family learned of the extent of his debt after his death. They were left in financial ruin, and now face years of poverty to pay back the amount owed. To make matters worse, they had to borrow more money to organize his funeral. Shivanna’s wife was forced to sell off her jewelry, including her thaali, the golden necklace Shivanna had tied around her neck at their marriage. Now all they are left with is a single buffalo cow, and get by selling the milk it produces.

“Only to plant the fields, it would cost him 25,000 rupees ($365) per acre, for the seedlings and the labour,” his father Kempegowda says, explaining that Shivanna had no relatives who could help him in the field and therefore was forced to hire laborers to help with the work.

He used expensive NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium) chemical fertilizers such as urea and “Suphala”, the mainstays of the Green Revolution. These cost tens of thousands of rupees per acre and are known to deplete the soil, reducing the yield and forcing the farmer to increase the amount used over time.

Harvesting the crop and transporting it to the factory where it is crushed to make sugar also take money. All these factors ate into Shivanna’s profits until he found himself borrowing more and more money to cover the costs, and eventually borrowing to pay previous debts.

When in 2014 his crops failed due to insufficient rain, he suffered a loss of 1 lakh ($1,490) in one hit. The following year, the price paid by the factory dropped from 2,000 rupees per ton of sugarcane to 1,500 rupees, some of which was not even paid – factories can take months to make payments, and when he died in July, Shivanna was still waiting to be paid for his January harvest.

Rathnamma Gowda’s house is located in the village of Chalegowdan Doddi, a short motorbike ride from Shivanna’s home. Her husband Mariappa committed suicide at the age of 45, after accumulating more than seven lakhs ($10,436) of debt.

“He said he was going to have a coffee at someone’s house,” she remembers, “and then he left and never came back. We found his body in his barren field. There had been no water because of drought, so he hadn’t been able to plant any sugarcane.”

Now Rathnamma works as a laborer, harvesting sugarcane for other farmers, and so does her son who was in his final year of college but had to drop out after his father died. “There are no good public colleges around, so we sent him to a private one, which cost us 15,000 rupees ($220) a year,” Rathnamma says. “Anyway now we need him to work in the fields, otherwise how are we ever going to repay the debts?”

The Karnataka JanaShakthi (KJS), a group of local researches, farmers and activists, produced a report on the suicides of sugarcane growers in the Mandya district, reaching the conclusion that “central to most of them are the issues of indebtedness and economic insecurity”.

One only has to look at the numbers farmers have told us about to understand the extent of this insecurity: on average, a farmer can hope for a yield of 40 tons per acre, with input costs such as seedlings, labour and fertilizers of about 40,000 rupees ($596). The maximum price currently paid by factories is 2,500 rupees per ton ($37), with about 800 rupees ($12) going to harvesting and transport costs, meaning a final profit of 28,000 rupees ($410) – a considerable amount of money. But yield can decrease to as little as 30 tons of sugarcane per acre and the price paid by factories can drop down to as little as 1,700 rupees per ton ($25), causing the farmer a loss of 13,000 rupees ($190).

With these narrow profit margins, which do not even include fixed costs such as hiring a tractor or leasing the land, it is extremely easy to fall into debt, and according to the KJS report, the average debt of the farmers who committed suicide was five lakhs ($7,455), a considerable amount when compared to about 18,000 rupees ($268) of average debt for the general population of Karnataka.

“It appears as though agricultural production [of sugarcane] is not a profitable one,” the study concludes. Yet, the farmers prefer to grow sugarcane instead of another crop, or food staples, which could be harvested to feed their families.

The stories of Shivanna and Rathnamma demonstrate how the farmers’ debt epidemic is multifaceted. In a country where public services and welfare safety nets are basically non-existent, money means security and the possibility to escape from the curse of a subsistence economy, which traps millions who barely earn enough for day-to-day living.

Shivanna was the only breadwinner in a family of eight, while Mariappa was trying to pay for his son’s private college, so that he might get a degree and have a different life. The debts they accumulated did not only come from farming, but included expenses for education, healthcare and housing.

This is because in order to guarantee a degree of security for their families, those fortunate enough to have some land use it to grow what they perceive as the most profitable crop – sugarcane. The alternative is to work for other farmers, as Rathnamma is now forced to do.

“We are paid two rupees per bundle of sugarcane,” says Kammalamma, a 55-year-old labourer who was harvesting crop in the village of Madhar Halli. “On a good day I can earn 200 rupees (about $3). But at least I always take some money home: the farmers earn much more, but they can also loose everything if the crop fails.”

As India slowly modernizes, lifestyles change and the cost of living increase as well, in what the KJS report describes as the “mushrooming of a peculiar rural middle class” in the Mandya district, where “per capita expenditure of farmers is more than their income”.

And middle class life doesn’t only cost too much: many young farmers are gradually shifting to the nuclear family, with young couples living on their own and sometimes moving to the cities in search of more opportunities and comforts. This reduces the labour available to farmers, who are then forced to hire laborers to replace their missing relatives, further increasing input costs and reducing profits.

Farmers also complain that the monsoon is becoming “erratic”, with less rain falling at the right time, threatening entire crops of sugarcane, a plant that requires a lot of water. With only about 42 percent of the Mandya district irrigated by the Krishna Raja Sagara dam, farmers are largely at the mercy of increasingly unreliable weather patterns, and many decide to dig their own wells.

Prasana Gowda is a 32-year-old sugarcane grower from the village of Hulivana. His grandfather had dug a small water cistern which has helped his family survive the unexpected droughts, and his brother also helps on the land, making the work much faster and the costs lower .Prasana tries to not use chemicals. Instead, he saves on costs by using his cows to plough the land and produce manure for fertilizer.

“I managed so far only because there is water cistern here,” he says, “otherwise it would have all dried up. I was always scared of taking loans, but now there is not enough water [to keep the water cistern full], so I will have to borrow one lakh rupees ($1,490) to dig my own bore well.”

Droughts are intensifying and occurring more often. In November 2016 the Karnataka government estimated the losses suffered by the agricultural sector over the last two years at more than 12,000 crores rupees ($1.7bn). Water has become another input cost in the farmers’ quest for security, whether through crop failure due to lack of water or by going into debt to irrigate farms.

And whatever security Indian farmers are looking for, it is hard to find it in the globalized markets of the 21st century.

The financial policies and reforms of the past decades have modernized all sectors of India’s economy, opening them up to foreign competition. As a result, small-scale Indian sugarcane growers find themselves competing with large-scale, industrialized plantations from places such as Brazil, where yields can reach 60 tons per acre, making it cheaper to import sugarcane from abroad than to buy it from local farmers.

Another central element of those neoliberal reforms has been to reduce the role of the government in the economy, reducing subsidies and deregulating prices to let the forces of the market work freely, causing wild fluctuations in the price of commodities.

When sugarcane exports were subsidized in the last few years, in an attempt to help the factories sell off their stocks of sugarcane and in turn be able to pay farmers and buy more sugarcane from them, Brazil filed a complaint at the World Trade Organization, arguing that such subsidies “distorted” the global market.

“By subsidizing exports, India reduces its domestic sugar stocks and helps local producers by propping up local prices above global levels,” the president of the Brazilian Sugarcane Industry Association said in a statement, but that meant producers in countries like Brazil “face even deeper losses because of depressed prices.

Their fate apparently inextricably linked to the financial fortunes of foreign investors, the Indian sugarcane growers can therefore expect limited support from a government anxious not to jeopardize its standing on the global markets, and are left to subsidize agriculture with their debts.

In the words of Vasu H.U., an activist from the KJS, “in the past, farmers worked with their relatives and their cows, which gave them manure to fertilize the fields – their families had an organic relationship with agriculture.” The changes brought about by modernity have broken this organic relationship, “and this break affected not only the families, but also our society, in which nobody cares about what happens to farmers.”

India’s is officially still a planned economy, and the 12th five year plan for 2012-2017 forecasts that the country’s urban population will almost double by the year 2030, reaching 600 million people. With the breathtaking growth of India’s urban, modernized middle-class, nobody seems to pay too much attention to the plight of the farmers of southern India, and the difficult choices they are faced with in today’s changing world.

published on Al Jazeera