For all those who consider food an important thing, and don’t want to eat out of plastic all the time, living in the city can be a contradiction. This is especially true for a vast city like Paris and for its numerous students, a category of people highly vulnerable to the food industry and its commercial priorities. In order to offer an alternative, groups of dedicated students have established collectives to buy organic produce together from farmers working the countryside around the French capital.

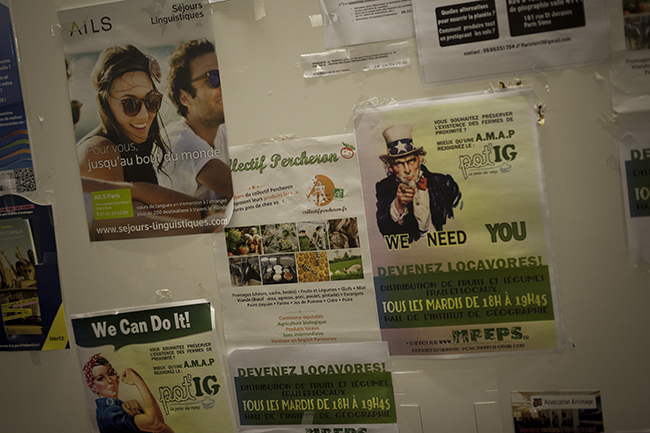

Numerous organizations set up by consumers distribute organic food and allow the demand to meet, get to know and cooperate with the supply, following the example of the nationwide system of AMAP (Associations for the Preservation of Peasant Agriculture). In the university of Paris, several AMAPs or similar groups are active, with hundreds of students buying organic vegetables “à la fac”, in the faculty building. One group is pot’IG, the buying group of the Institute of Geography, which every tuesday delivers “bio” products to about 60 people.

It works around the concept of the panier, the food basket: a group of consumers commits to buying regularly a basket of produce. The idea is to pay in advance as much as possible, and to accept a certain degree of variability in the contents of the basket, in order to give some financial security to the producer and to adapt to the natural cycles of its work – with these two things, the producer and the natural processes he or she works with, regarded as intrinsically important and worth paying for by the consumer.

How this happens can take many forms, as witnessed by the different approaches implemented by the various groups set up by Parisian students. Traditionally an AMAP distributes the products of more than one farmer, with all of them being certified organic and the delivery physically carried out in turns by members of the group. Others buy from only one farmer, and in some group not all the products are organic, whether in practice or on paper. The contents of the basket are never the same, and change according to the region, the season, and the level of sophistication of the whole operation.

While similar groups can literally feed an entire family and provide work for entire farms in the countryside, things are a bit different in the cities, and especially in a university. Many groups take years to establish a reliable consumer base, students are poor and then they go on holidays, preventing the relationship with the producer from growing stronger. As a result, the baskets can be more expensive, and find it hard to compete in terms of prices and variety with the ever present chains of supermarket which have a huge presence in French cities.

The question of whether it is actually possible to feed the city with similar practices remains, and most likely revolves around wider changes in the lives of its inhabitants, the work they do and its retribution, and in the general hierarchy of priorities we assign to things. In times of crisis, it can be hard to decide to spend more money on a little vegetables or a bottle of fine apple cider, yet it might be the case that the crisis itself, which today restricts our choices, is a consequence of choosing profit, or saving money, over quality, and eating good food.