Jerusalem, Israel – 26th of May, 2013: Soldiers of the Nahal Haredi battalion, a religiously observant unit of the IDF, take part in their swearing-in ceremony at the Givat Hatachmoshet (Ammunition Hill) museum.

While religious Jews have always served in the IDF and are currently highly present in officer corps and special units, the haredim have traditionally stayed away from serving in Israel’s universal-conscription army, which they see as a distraction from their main goal in life: studying the Torah and obeying all its mitzvot (commandments). Exempt from Israel’s universal draft thanks to a long series of coalition agreements between their political parties’ and the secular ones, the haredim therefore do not take part in one of the experiences which define being Israeli, the army service.

Brought up in separate communities, studying in a separate school-system and living in separate neighbourhoods, the haredim embark on a completely different life track from that of their secular brethren, feeding a process of mutual estrangement which has led to shocking levels of hostility among the hiloni (secular) and haredi sectors. In a country where the first thing a hitchhiker is asked after being picked up is “which unit did you serve in”, and in which 18 years old kids put their life on hold for up to four years, being exempted from the draft has become a symbol of the haredim‘s alienation from Israeli society.

On the other hand, those separate communities, school-system, and neighbuorhoods are there for a reason. For the stricly observant haredi youth, it is not an easy thing to serve in the IDF, or living in a secular neighbourhood for that matter. Due to their education in a school system which prioritizes religious texts, most haredim would actually perform quite badly in the IDF’s entry examinations, and stand little chance to join combat units. Additionally, the secular imprint of the IDF, and especially its strongly mixed-gender structure, pose a myriad of hazards to the haredi‘s lifestyle based on halacha (Jewish religious law).

In an attempt to allow at least some haredi youth to join in the defence of the country and partake in the employment opportunities offered by serving, the IDF set up a special unit for religious soldiers, the Netzah Yehuda Battalion, known as the Nahal Haredi. Part of the West Bank based Kfir Brigade, the Nahal Haredi aims to “provide for the unique spiritual needs of Haredi youth” and give them “educational and professional qualifications needed to achieve economic independence”, with the aim of “bridging the social gap between the secular and religious populations in Israel”.

The swearing-in ceremony, in which the new soldiers are given a rifle and a Torah, is a rite of passage through which all combat soldiers go through. Usually held in evocative places such as the Kotel or army memorials, these ceremonies are open to the public and are attended by the soldiers’ families and friends. Due to heated debate on the conscription of haredi youth currently taking place, and the vehement opposition of some haredi groups to any form of cooperation with the IDF, this year’s Nahal Haredi public swearing-in ceremony was postponed because of the fear of violent protests, and almost cancelled altogether.

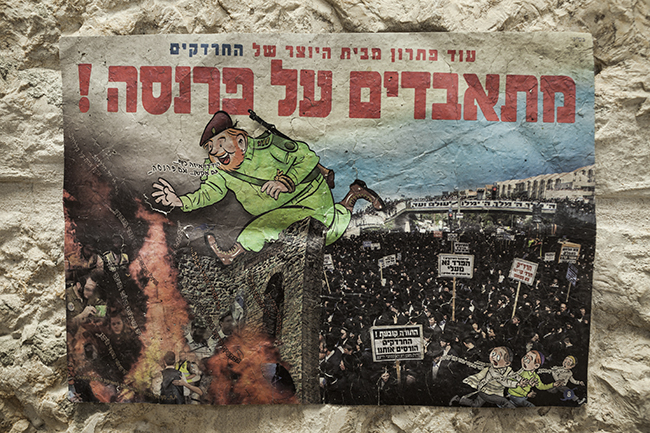

A flyer distributed at demonstrations against the enlistment of Haredim and posted on the walls of religious neighbourhoods shows haredi children running away from a rapacious IDF soldier, as haredi masses form a wall against the betrayal of the “hardakim” (a play on the Hebrew word for insects), the “frivolous haredi” who have left the way of Torah to join the Nahal Haredi. Haredi youth who chose to enlist have been denounced as traitors and collaborators and face immense pressure within haredi society, with some even physically attacked or cast out from their communities.

Hundreds of relatives, friends and supporters attended the ceremony, held at the Givat Hatachmoshet museum which commemorates the 1967 battle of Aummunition Hill, with many holding placards reading “haredi soldiers are our brothers”, in a show of solidarity for the Nahal Haredi recruits.

Established in 1991 with just 30 soldiers, the Nahal Haredi grew to a full battalion of 1,000 active soldiers at any given time, and serves as a laboratory where to “develop and implement programming designed to provide military, education and economic opportunity” to the haredi community. However, there is one difference between this unit and most others: these soldiers have not drafted, but have chosen to serve voluntary, with the battalion actively seeking out new recruits even among Jewish communities abroad.

Based on the belief that military strength must be accompanied by the spirit of Torah and Mitzvot, the Nahal Haredi strives to live up to its motto, a commandment from the Torah which mandates that “your [military] camp shall be holy”, related to biblical practice of keeping military camps sin-free in exchange for Divine protection in battle. Rabbis take part in all of the battalion’s activities, offering guidance and counselling to the soldiers, while others work with halachic authorities to find new ways to maintain religious observance while not compromising combat effectiveness.

The entry criteria to the Nahal Haredi are simple: Shabbat observance, wearing a kippah (skullcap) and “a refined speech”, which basically means proficiency in Hebrew, a requirement which effectively bars entry to the thousands of haredi youth who speak the language very poorly, having grown up in Yiddish-speaking communities. Under the watchful eye of the rabbis and with a daily schedule which includes time for prayer and shiurim (religious lessons) on the importance of fighting for the People and the Land of Israel, the Nahal Haredi aims to turn its recruits into today’s “warriors of King David”.

The Nahal Haredi is supported by a non-profit organization devoted to raising the funds required to meet its strict religious standards and to offer the soldiers a one-year vocational training instead of a third year of service, things which other soldiers do not enjoy and which the IDF has somewhat refrained from paying for. This is usually explained with the experimental nature of the battalion, and its value as a showcase of a future integration of all the haredim into the IDF. The battalion’s stated aims are to enhance “the perception of haredim within Israeli society” and to serve “as ambassadors of their community”.

A unit specifically established to accommodate every need of a specific sector of society might seem strange for the famously egalitarian IDF, which always fashioned itself as a people’s army in which everybody serves equally. However the growing fragmentation of Israeli society, increasingly divided alongside religious, ethnic and social fault lines, is beginning to threaten the very foundations of Israeli society, leading the IDF to intensify its efforts to serve as society’s equalizer, with units such as the Nahal Haredi “bridging the societal gap, standing proud for an ideal that brings unity to our people”.

A Nahal Haredi pictured with its two children at the end of the swearing-in ceremony. One of the main differences making integration into the IDF difficult is the haredi emphasis on marrying and establishing a family very early. Serving for three years (and eventually going on a one year trip to India or South America after the service, like most Israelis do) is completely unthinkable for most haredi youth, and most likely would also affect their chances to be allowed to marry a woman from a good family.

So far, and judging from the physical appearance of its soldiers, the Nahal Haredi seems to have made little headway in recruiting from those haredi communities for whose enlistment the secular public is calling for. Many Nahal Haredi recruits are actually not haredi in the strict, black-hat wearing sense, and come from Zionist backgrounds such as Dati Leumi, the National Religious society which makes up the large part of the ideological West Bank settlers and already overwhelmingly serves in the IDF, and “hardal”, the “Haredi Dati Leumi” sector, composed of Religious Zionists who in their search for a stricter religious observance are moving closer to a haredi lifestyle.

For all its value in fostering integration within Israeli society and unity among the Jewish people, the establishment of specifically religious units within the IDF remains controversial, as was show last year when a group of Nahal Haredi walked out of a military ceremony which featured female singers, whose voice is regarded by haredi as a sinful temptation, with some rabbis going as far as saying that a true haredi soldier would die rather than hearing a woman sing. Paradoxically, the integration of haredim into the IDF might come at the cost of the exclusion of women, in a trend that is affecting the whole of Israeli society.

Additionally, there are issues as to where the loyalties of these soldiers exactly lie, after having grown up (and now also doing their army service) within a context that places the Torah and the rabbis above everything else, including democratic values and in some cases even human rights. It remains to be seen if the IDF will be able to combine accommodating to the haredim‘s religious lifestyle with its nature as a democratic, egalitarian people’s army, a challenge that after all underlies the entire Zionist project: creating a society in which all Jews, with all their thousands of differences and disagreements, can somehow get along with each other.