Watching the events that are currently unfolding in Israel and Palestine, we are witnessing a chain of events that we have already seen many times in our short lives. The conflict over the land between the river and the sea is in made up of a lot of different stories and tragedies, yet the same things and the same themes keep repeating themselves, in a endless cycle of violence with only slight “new variations to the same old shit”, as an Israeli friend of mine put it the other day.

It usually begins with a period of quiet, except the quiet is only apparent, while the tension between Jews and Palestinians grows because of the overall situation, of historic and unresolved issues, or of ongoing acts of aggression such as the establishment of new settlements, terrorist attacks and racist incidents, usually in Jerusalem. This tension eventually leads to protests and violent clashes, also usually in Jerusalem or in some other symbolic place such as the fence around Gaza, which bring the tension into the open and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict back on the news, both in Israel and abroad.

All of this usually happens in the context of something else, such as a political crisis in Israel, usually related to Benjamin Netanyahu’s efforts to remain prime minister, or to squabbles in the Palestinian and Arab leadership. And just as the protests reach a critical point, making people wonder if something is really about to change, there is an “escalation” in Gaza, and everything takes a turn for the worse.

We all know what the situation in Gaza is, so it is easy to understand why it takes very little for things to “escalate” there. Once that happens, within a few hours the original protests and the issues behind them are completely forgotten as the grim bodycount sets in motion, with each hit on a house or a school in Israel and each obliterated Palestinian family hardening the respective positions and taking us closer to a “war”, which usually means a period in which Gaza is bombed day and night, and rockets are fired at cities in the south of Israel. There might be slight variations such as a ground invasion of the coastal strip or rockets falling on Tel Aviv, but the format remains essentially the same, as does its astonishing ability to completely put Israeli society on a war footing in a matter of days.

This format was on full display in recent weeks. After one year and a half of the Coronavirus pandemic obscuring every other issue in the world, including the situation in Israel and Palestine, a new wave of mobilisation in Jerusalem was sparked by the impending eviction of Palestinian families in the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood, to make room for Israeli settlers. Weekly protests against these evictions have been held for more than a decade, yet they grew bigger this time, in turn leading to growing repression by Israeli security forces. All of this happened as Israel is gripped by an unprecedented political crisis that led to three elections in the span of a year, and during the celebrations for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, with large masses of Palestinians gathering in Jerusalem to pray at the Al-Aqsa mosque and to hang out at Damascus Gate, the symbolical and commercial heart of East Jerusalem, which Palestinians see as their capital. In a city where 40% of the population considers itself under the military occupation of Israeli security forces, and with tensions already running high because of the events in Sheikh Jarrah and a string of racial incidents captured on TikTok, the Israeli authorities made the situation worse by putting up makeshift checkpoints at Damascus Gate, only to be forced to remove them after two weeks of protests. Emboldened by this small victory, the protesters kept up the pressure, encountering more and more police repression and eventually leading to violent clashes on Temple Mount and at the Al-Aqsa mosque.

Stoked by images of Israeli police attacking worshippers on what is Islam’s third holiest site and the centre of Palestinian national consciousness, the unrest spread all across the land, with Palestinians protesting at the border fence around Gaza and in other Palestinian communities inside Israel, whose members have full Israeli citizenship and are usually not too involved in the struggles of Palestinians in Jerusalem or in the West Bank and Gaza, while Hamas fired some rockets and threatened to launch more if Israel kept attacking the holy sites of Jerusalem. The Israeli police remained in the streets in massive numbers, and as the protests gathered momentum, the situation seemed destined to come to a head this Monday, the day of the Jewish calendar known as Yom Yerushalayim (Jerusalem Day), that commemorates the conquest of East Jerusalem in 1967 and is celebrated by nationalist Israelis with a provocative march through Damascus gate that inevitably always leads to clashes with Palestinians. With violence already raging across the city, Israeli authorities announced the re-routing the march away from Damascus Gate in order to avoid having to deal with too many troubles, marking an unprecedented success for the young and unarmed protesters.

It did not last long, it never does, the violence continued and within a few hours Hamas was launching volleys of rockets from Gaza, going as far as targeting Jerusalem itself. Rockets are sporadically launched from Gaza all the time, just as the Israeli air force occasionally bombs the coastal strip all the time, but for some strange reason targeting major cities in central Israel is regarded as taboo, maybe because of its power to break the illusions of Israelis in Tel Aviv that they live in a “normal” country. Air raid sirens echoed through Jerusalem, leading to the evacuation of the Israeli parliament and immediately changing the narrative from one of unarmed protesters versus the police to an open, military confrontation between the state of Israel and the terrorist organisation of Hamas. The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) immediately retaliated with bombs, houses in the south of Israel have been hit, and global opinion quickly shifted from urging “restraint” on Israel’s security forces to re-affirming the “country’s right to defend itself” while people began to die on both sides, and with the usual ratio between the two.

The Israeli political crisis instantly lost much of its urgency, and while just a few hours earlier even the Israeli media wondered about the wisdom of the conduct of the police in Jerusalem, and some on the Israeli left timidly began to debate how to join the growing mobilisation, now it’s all about the need for strong leadership, the debating of military options, the calling up of army reserves, and announcements by the chief of staff of the IDF about an “indefinite escalation”, while Israeli moderates on Facebook declare their opposition to all forms of violence. We have seen it all before, and we shall undoubtedly see it again in the future, at least until the fundamental unbalances that separate Israelis and Palestinians are resolved.

One of the strongest of these unbalances is the one in military capabilities, which makes dealing with a usually one-sided “war” against Hamas much easier for Israel than the complex task of suppressing unarmed protesters in the centre of Jerusalem, a popular tourist destination revered by as many as three worldwide religions. Neither tourists nor pilgrims of any religion go to Gaza, and while in Jerusalem casualties are usually to be avoided, lest they inflame the situation further or affect Israel’s international reputation, when it comes to Gaza killing people is actually the objective, as part of what in Israel is openly described as “mowing the lawn”, the act of periodically destroying the territory’s militant organisations and some of its buildings in order to keep the place quiet in the absence of a political resolution to the conflict, all with the more or less tacit approval of most of the world until the inevitable ceasefire puts an end to the bombing. This specific aspect of the recurring “wars” with Gaza is so openly accepted in Israeli society that when the IDF chief of staff during the last round of 2014, Benny Gantz, ran for prime minister five years later, he put out a campaign ad for that consisted exclusively of the number of Palestinians killed in the fighting with footage of funerals on the background, of course claiming that those 1,364 specific dead Palestinians were all terrorists.

A minor tradition in this recurrent chain of events is the IDF announcing the name of the military operation meant to deal with this new round of violent conflict. The first one that I remember is mivtza Homat Magen (operation Defensive Shield), which was the codeword for the military repression of the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2002. After the shock and horror of that bloodbath, and decades of colonisation and pacification of the West Bank, the brunt of Palestinian armed resistance and of the ensuing Israeli military operations shifted to Gaza, beginning the series of nearly identical confrontations that continues to this day: among others, I remember mivtza Gishmey Kaitz (operation Summer Rains) of 2006, mivtza Oferet Yetzucha (operation Cast Lead) of 2009, mivtza Amud Anan (operation Pillar of Defence) of 2012, and then mivtza Tzuk Eitan (operation Defensive Edge), which followed a very similar chain of events in Jerusalem in 2014.

Maybe the Israeli army has a list of possible scary-sounding names for future military operations, or maybe they are chosen on the spot by someone in an office at the IDF’s headquarters in Tel Aviv, yet these apparently random words stick in Israeli consciousness as the name for that specific round of violence, and they all have a specific meaning, usually referencing a passage in the Torah.

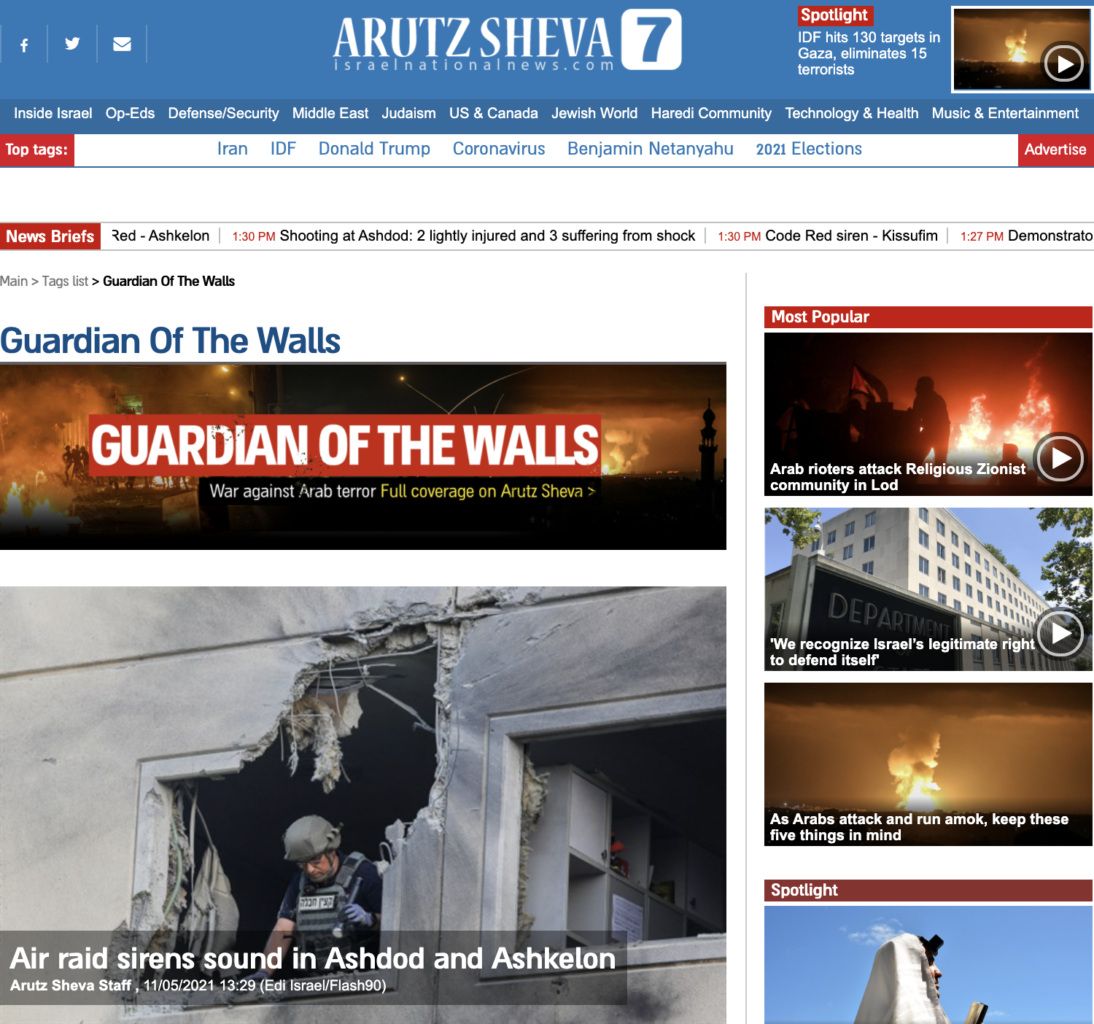

This year’s war is to be known as mivtza Shomer Hachomot, operation “Guardian of the Walls”, as announced by the spokesperson of the IDF in a tweet that ended with “We will guard the walls and the skies and defend Israel.”

With the country established on what essentially was and still remains hostile territory, guarding walls is a central element in the history of Israel and in the lives of its Jewish inhabitants, many of whom have actually spent parts of those lives in a uniform, watching over a checkpoint, a settlement, or the country’s contested borders with its hostile neighbours. This undoubtedly necessary and unique aspect of the Israeli experience is the theme of a famous Israeli song from 1977 that is also titled “Guardian of the Walls”, and was originally performed by one of the IDF’s military bands, which used to be very popular and launched the careers of many of Israel’s pop singers and musicians.

The song tells the story of an Israeli soldier stationed in Jerusalem, as he watches the Old City from its walls and remembers when in school he was taught the passage in the Torah’s Book of Isaiah about putting guardians on the walls of Jerusalem, and how he ended up being of those guards. While he is on duty, he listens to the voices of the city, to the sounds of the market, of the street vendors and even to the call of the muezzin, which can be heard across most of Jerusalem, and especially around its Palestinian quarters where most soldiers and policemen inevitably find themselves standing guard. The lyrics are quite sad, with the lonely guardian declaring his love for the city while complaining about having to watch out for explosive grenades and shivering with cold, as the sun sets and he dreams of a time in which “we will no longer need guards…”

At the time this song was quite a hit, and in 2016 a cover was made by pop singer Lior Farhi. The video features images of the singer against the backdrop of Jerusalem’s golden Dome of the Rock, the mosque on Temple Mount that was at the center of the protests which led to this escalation, mixed with images of a child wandering the streets and mostly interacting with the ever-present Israeli security forces that guard them, and which are one of the very reasons protests are taking place at all.

While at least the guardian in the song seems to be having second thoughts about standing around with a weapon in Jerusalem, and expresses his hope for a day when this will no longer be necessary, the endless repetition of totally predictable outbursts of violence such as the one we are witnessing now, which everybody knows it will yield no real results besides more dead to be avenged in the future and a brief period of uneasy quiet, makes the realisation of such hopes very difficult, and might actually be having the opposite effect, just like the armed soldiers guarding every corner of East Jerusalem have actively contributed to set this cycle of violence in motion.

None of these so-called “wars” has solved any of the problems that afflict both Israelis and Palestinians, so they must serve other purposes, such as creating the illusion of “peace” by regularly breaking it with outburst of pointless violence, or allowing the Israeli leadership to score shallow victories and to terrorise the Palestinians into submission for a little longer. They also allow the hardliners on both sides to display their fighting spirit and show off their latest weaponry, while the moderates and the sympathetic international community can once again mobilise for a ceasefire that only restores the status quo, instead of working on a durable peace which is impossible to achieve without seriously challenging that very same status quo, and can also show off their concern for civilian casualties or “international law”, all while houses are getting bombed left and right and people are dying in droves. Useless to say, all of this makes the violent repression of unarmed protesters an almost irrelevant afterthought, allowing the Israeli authorities to stamp out a growing and possibly dangerous protest movement, and in turn reinforcing the claim of militant organisations such as Hamas to be the sole defenders of Palestinians in the face of Israeli aggression.

Especially in these violent days, it is hard to make sense of this endless cycle, and of a country whose youth sing of standing guard over walls and another people. Once again, we are faced with the same old question that haunts the state of Israel and those who live in its shadow: are these pointless outbursts of violence and this obsession with guarding walls simply the result of Israel’s history of conflict, or are they fundamental practices in Israeli society and identity that actually sustain this conflict, leading to more outburst of violence and to the need for even more guards and walls?