Driving into Jerusalem from the coast, just before the gates of the city lies a ghost village: Lifta. For thousands of years, many different people inhabited these steep slopes and many armies have passed through them on their way to Jerusalem, whose old city is but a few hills away, often not with the best of intentions. The last stable residents were forced to leave during the civil war of 1948, and since then the houses of Lifta have been slowly crumbling away. However, the history of the village did not end there, and today the place is far from empty.

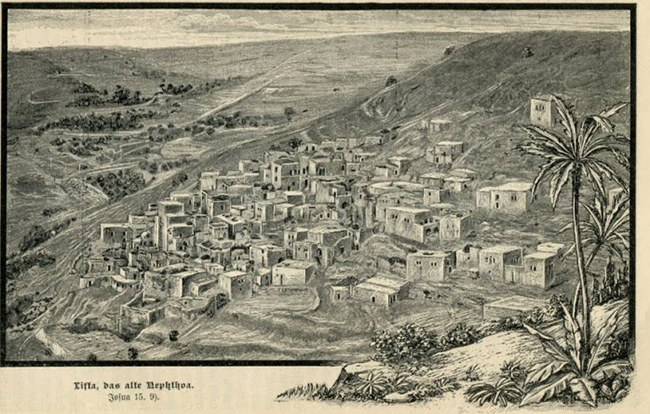

A German illustration from the end of the 19th century records the village in its better days, half a century before its downfall. Established more than 2,500 years ago, when it was called Mein Neftoach, the village is mentioned in the Torah as the northernmost possession of the tribe of Judah. Like most of the Land of Israel, it was destroyed by the Roman legions which eventually also destroyed Jerusalem. Crusaders returned to the village, which they referred to as Clepsta, and by the year 1569 some 400 people where register to live there by the Ottoman Authorities, in the village of Lifta.

Its history would be quite typical of many in Palestine, and would include a long succession of armed invasions: it was violently occupied in 1834 because of its resistance to Egyptian rule, while in 1917 its inhabitants chose to open its gates to the conquering British soldiers, raising white flags. Its population grew quickly under the British Mandate, thanks to a period of economic expansion also due to the steady development of the Zionist enterprise, going from 1,500 in 1922 to almost 3,000 in 1948, with about one tenth of the land owned and inhabited by Jews and the rest by Arabs.

Things fell apart as civil war among the Jewish and Palestinian communities broke out, with the village sitting right by the main artery connecting Jerusalem to the coast and the main Jewish settlements, whose traffic came increasingly under attack by Arab fighters. In 1947 a resident of Lifta who had allegedly spied on Jewish convoys was killed, and on the 28th of February a small group of underground Jewish fighters, the Stern Gang, attacked a coffee-house in the village, killing six people and wounding seven others. By February next year, the village was empty.

In the following months, which saw total warfare between the rising Jewish state and an Arab coalition made up of foreign soldiers and Palestinian fighters, Lifta was demolished, with about 50 structures left standing which make it one of the few depopulated Palestinian villages to not have been completely erased. Some of its inhabitants who during the fighting moved to communities on the other side of the valley were barred by Israeli authorities from returning to their homes, and would be forced to watch them crumble.

As Jewish Jerusalem expanded, the ruined village became a deserted corner between two of the main highways to the city, and turned into a shelter for a variety of people. In 1984, an Israeli terrorist organization know as “the Jewish Underground” used it as a base from which to plot the destruction of the Al-Aqsa mosques, and various groups of hippies, runaways and drug addicts have inhabited it, establishing a stable presence which today also includes many ultra-orthodox youth whom, for one reason or another, need a place and some quiet.

Declared a nature reserve in 1959, Lifta was renamed Ein Neftoach, as Israeli authorities sought to bring back to light the country’s biblical past. As with many places in Jerusalem, the old name somewhat stuck, even as the village’s spring became a popular hangout spot for Jerusalemites, who on a hot a day are always looking for a spring. The memory of Lifta was preserved by its refugees, who to this day reclaim their right to return and have established the Lifta Society, based in Chicago in order to keep its identity alive and continue it with events and activities.

In 2006 a plan was approved to gentrify the site, turning it into an upscale development with a hotel and a shopping mall, although in the words of its architect, the place’s “genetic code” would be preserved by building “something as authentic as possible.” Even the Society for the Preservation of Israeli Heritage Sites joined the opposition to the plan, which was shelved in 2011, leaving Lifta in a limbo, its ruined houses largely empty and its spring echoing with the voices of families and couples who enjoy the beauty of this hidden corner of Jerusalem, yet might be completely unaware of its violent history.