One of hundreds of boats used by migrants to cross the Mediterranean sea lies abandoned in the harbour of Portopalo di Capo Passero, Sicily’s southernmost community. The stretch of sea between the island and north-Africa, known in Arabic as Madiq Qilibiyah (strait of Kelibia), is crossed every year by thousands of migrants on their way to Europe. Many of the boats they sail on, usually former fishing boats sold for scrap and often basically unseaworthy, end up abandoned on the Sicilian shores.

Around the year 1080, the Sicilian poet Ibn Hamdis was forced to leave his beloved island by the Norman conquest and seek refuge in Andalusia. “The crossing at sea”, he wrote in one of his many nostalgic poems on his misfortunes, “wasn’t harder than the events which forced the journey upon you”. Ten centuries after, thousands of people are caught up in such bad events that they decide to risk their lives and take to the Mediterranean, crossing the sea on their journey to Europe.

According to their testimonies, the migrants spend days on these small fishing boats, completely at the mercy of the sea and the boat’s crew members. However most people in Sicily explain that such small boats cannot carry enough fuel to make the journey, and in any case appear too clean to have been used by hundreds over several days, and are therefore most likely towed near the European shores by larger “mother-ships”, some of which have indeed been intercepted by police in an attempt to shut down the trade.

According to the local fishermen, boats such as this one sinking in the port of Marzamemi, are old, disarmed fishing boats, most likely at the end of their career and definitely not safe for such a long sail. North-African ship-owners probably save some good money in selling them rather than having to scrap them, an activity which will eventually have to be paid for by Italian taxpayers, when and if the Italian authorities do take care of what is a growing presence across the small ports of Southern Sicily.

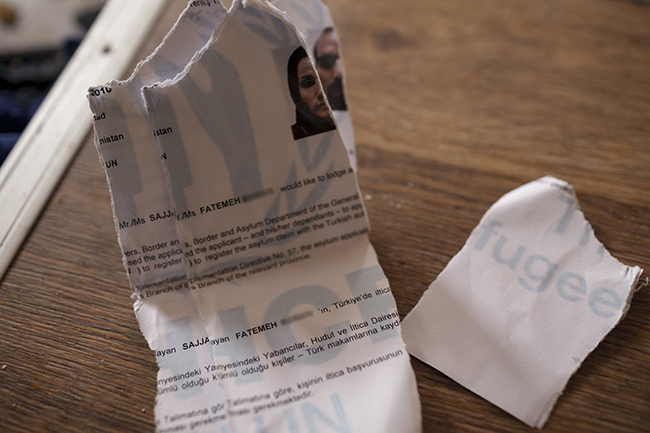

Possibly to avoid being identified by Italian authorities, a group of refugees from Afghanistan disposed on the boat of the applications for asylum they had filed in Turkey. While the journey might be uncertain and largely determined by opportunity, the destination is sometimes clear, with many trying to reach relatives and friends that have gone before and can help in resettling in a new country. Family reunions are not always allowed, and the European Dublin Law forces migrants to remain in the country where they ask for asylum.

More often than not the boats break down during the crossing, leaving their passengers stranded at sea for days until they are rescued by someone on the other side. With each migrant paying up to 5,000 dollars for the trip, usually in advance, and hundreds of boats crossing every year, this is a lucrative business which guarantees huge profits to organized criminals who do not appear to give much importance to the lives of those who are forced to turn to them.

At the European end of the crossing, the boats are the responsibility of local Coast Guard commanders such as Luca Sancilio, head of the port of Siracusa, who are tasked with making sure that the migrants which are sighted make it to shore safely, whether on their own or after having been rescued. “We exist to safeguard human lives”, he said on his vast powers in dealing with emergencies at sea, such as ordering any other ship to offer assistance to those in distress, “which is the first law of the sea”.

Boxes of instant noodles found below deck on a large boat used by migrants, whose rudder had been disabled by the crew members as they abandoned the ship and its passengers. The growth of migration across the Mediterranean, legal or otherwise, attests to both the historic difficulty of sealing this narrow sea, with its narrow straits and thousands of kilometres of accessible shores, and to a pressing need for a lot of people to get to the other side, which is met by those who have boats and the will to put so many lives at risk for profit.

After the end of their journey, the boats are confiscated by Italian authorities, who also try to individuate the crew members among those who disembark, who are often of many different nationalities and do not know each other. Italian legislation mandates harsh sentences for anybody who assist illegal immigration, in an attempt to stem the flow of boats which has even saw Sicilian fishermen who rescued migrants at sea charged by police and temporarily lose their fishing vessels and their means to make a living.

Medicinals against sea sickness left on a boat by migrants, most of whom recall their time at sea as an extremely scary experience, well known to be a mortally dangerous one. Thousands have died in a long series of shipwrecks, fires and even tragic collisions with Italian police boats, yet many more remain willing to face storms, thirst, sharks and the vast sea in order to come to Europe. For many, however, the crossing is just a small part of a long journey that has taken them through deserts, war zones or prisons.

While the journey has been more or less the same over the ages, the reasons for which people cross the Mediterranean are many and diverse. There are Syrian refugees who can afford the trip to Europe, Tunisian teenagers who have jumped at the first opportunity to seek work, and others who are fleeing famine or violence. European immigration authorities try to distinguish among those coming to grant asylum to some, in compliance with international law, while keeping as many as possible outside the borders of Europe.

What eventually happened to the migrants who came on these boats is unknown, some must have reached their final destination while others are still detained, or might even have been repatriated, possibly to try another time. However, the boats lining up on the shores of Sicily can attest only to those who made it safely to shore, while the stories of those who weren’t so fortunate are lost at the bottom of the Mediterranean, alongside the wrecks of thousands of boats exactly like these.