Naples, Italy – 16th of November, 2013: Demonstrators take to the streets of Naples to call for an end to environmental devastation of Campania, an Italian region plagued by illegal dumping of toxic waste and disastrous management of garbage disposal. In recent months, the never-ending issue of Campania and garbage returned to the spotlight, with a new wave of popular mobilization which culminated in a regional demonstration, organized under the banner of #fiumeinpiena (flooding river).

The destruction of Campania, the southern Italian region surrounding Naples, is a disaster that has been going on for decades. A combination of poor governance, criminal activity and typical southern laissez-faire has reduced entire swathes of the region to a toxic wasteland, poisoned beyond hope by thousands of legal and illegal dumping grounds in which unspeakable things have been disposed of for the profit of organized criminals and their accomplices in the public administration.

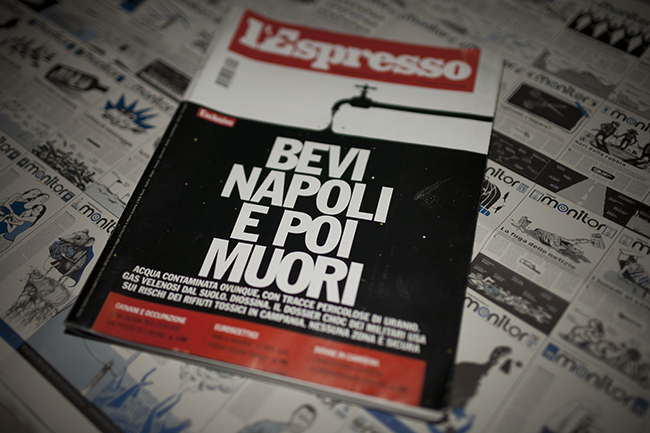

“Drink Naples and die”, reads a cover story on a study of the alarming pollution levels in the city’s water system. After a series of new revelations, the issue of Campania’s pollution is mainstream once again. But past experience of waves of public awareness has made many suspicious that a new “emergency” is in the making, possibly to speculate on the next big business, the cleaning-up operations. The major of Naples was also quick to condemn the media’s sensationalism, arguing that it is not the case that if you drink Naples’s water, you die immediately.

At the heart of the issue is the question of who is responsible for the disaster. While local activists have been denouncing the network of complicities that has ruled the region for decades, the recent wave of mobilization took a more abstract approach, shifting the focus on impersonal entities such as the “land of the fires”, referring to the areas where toxic waste is incinerated in the open, or the “biocide”, a new word to describe the destruction through pollution of both the land and of the life that inhabits it.

Many have profited from using Campania as an unregulated dumping ground: northern industries have disposed of their toxic waste at low prices, politicians have speculated on the long series of “garbage emergencies”, and local criminals have made millions out of one of Italy’s most successful business enterprises. But where was the public while this happened? Can we really claim that the people did not know or understand what was happening, day after day and over an entire region?

Whether this new movement will be successful in its efforts to finally awaken public opinion, stop the devastation and force the authorities to begin the long process of cleaning up the mess, will largely depend on its ability to defend the territory on the ground rather than on the media, which just as they have picked the story up for a few weeks, might bury it once other topics become more popular. With tens of thousands of people dying of mysterious diseases and all sorts of poisons festering through the land, time is definitely running out.