Over the course of three days at the end of May, Israeli authorities held a nationwide drill of the Home Front Command, the IDF’s unit tasked with protecting Israel’s civilian population, testing and displaying its capabilities to respond to what has become the Middle East’s most popular way to wage war against Israel: shooting rockets at it. With the IDF more or less maintaining its supremacy on the battlefield and the air force fully capable of bombing pretty much anything Israel’s leadership wants it to bomb, targeting its population centres has become the only way for the country’s enemies to retain some strategic leverage against it.

Israeli civilians have found themselves increasingly under fire in recent years: in 1991 tens of Iraqi SCUD missiles fell on Tel Aviv, in 2006 thousands of katiushas fired by Hezbollah paralysed the north of the country for more than month, and increasingly deadlier rockets have been coming from Gaza for years, eventually reaching the country’s centre in 2012. It has become the price Israel has to pay each time it goes to war, and the ability to pay it without too many casualties has become crucial to maintain the country’s morale and its will to keep fighting until the IDF has achieved its objectives.

Established after the trauma of the 1991 Gulf War, when the possibility of Saddam Hussein making good on his threat to bomb Tel Aviv with chemical weapons confined an entire generation of Israeli children to the shelters with gas masks and bamba (Israel’s most popular, peanut butter-based snack), the Home Front Command is tasked with preparing the civilian population to deal with potential emergencies and with protecting and rescuing it when these emergencies do happen, through a vast array of warning systems, bomb shelters and search & rescue units. Both in times of peace and of war, the Home Front Command’s only purpose is to save lives, or at least to reduce deaths as much as possible.

While other units of the IDF can dream to achieve glory on the battlefield by defeating the enemy, the Home Front Command deals mostly with bad stuff. 65 years after its establishment, Israel still does not have much friends beyond its borders, and as rockets get cheaper and more easily available in an increasingly unstable Middle East, Israeli cities coming under sustained fire during a conflict is taken for granted. Speculating about an attack on Iran’s nuclear capabilities, Defence Minister Ehud Barak commented that the cost of the inevitable retaliation would have been of “not even 500 casualties”, leaving Israelis to wonder if that was a small or a large number.

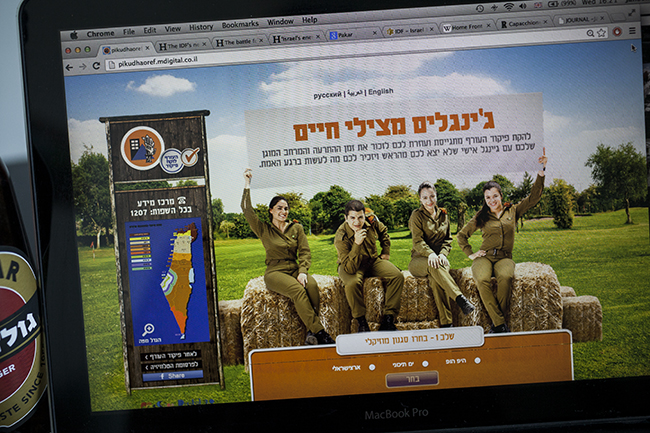

The basis of civil defence is compliance with orders, and the Home Front Command has been investing a lot of resources in making sure the population is aware of the threat and prepared to follow instructions. In a somewhat controversial move, an internet app was unveiled during the latest drill which sings a jingle telling people how much time they have to go to their nearest bomb shelter based on where they live. Maybe in an attempt to connect with Israel’s various population groups, one can choose the jingle’s musical style to be either hip-hop, traditional Israeli folk or an unspecified “Mediterranean”.

The closest miklat ziburi (public bomb shelter) to my house, in Jerusalem’s Musrara neighbourhood. Public and private bomb shelters are available all across Israel, although they are not always in good conditions and thousands of buildings don’t have one, especially in poor areas. Additionally, all new housing must be equipped with a mamad, a reinforced room capable of withstanding rockets and chemical attacks. During the last drill, the population was told to go to these shelters when the sirens rang in order to practice their response, something which most people actually refrained from doing unless they found themselves in a public building, where the drill was somewhat enforced.

An Israeli social worker collects gas masks for the residents of a shelter for people with mental illnesses at a distribution point set up last year in Jerusalem’s main shopping mall. The Israeli authorities periodically distribute gas masks to the population, at the cost of millions of shekels, and all Israelis are supposed to have one at home at all times. Combined with the ever-present risk of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons and the memories of 1991, the possibility of a catastrophic unconventional attack with thousands of casualties is always somewhere in the background of public discourse, and has almost replaced the old “Arabs throwing us into the sea” as the most popular worst case scenario.

Reserve soldiers from the Home Front Command are briefed before simulating the rescue of victims from a building hit by a rocket in Nazareth Illith, in northern Israel. With a somewhat more laid back attitude marked by the near absence of weapons among its ranks and its emphasis on saving people, the Home Front Command is quite different from the other units of the IDF. Many Israelis who choose to do reserve duty throughout their life but no longer want to serve in combat units, be it because of having had children or of changes in political attitudes, ask to be transferred to the Home Front Command.

As is the case with most units of the IDF, in the Home Front Command men and women serve together, and the unit has a high percentage of girls among its conscripted soldiers. In a society where in which army unit one has served in is an extremely important factor in determining job opportunities, social status and the possibility of a political career, the Home Front Command is still not regarded as a very prestigious unit, mostly because of the emotional attachment to combat units which is still very strong in Israel.

The search and rescue units of the Home Front Command are known for their efficiency and have been sent to offer humanitarian relief all across the world. When an earthquake devastated much of Haiti in 2010, the IDF set up a field hospital which saved countless lives, and still is a major talking point in the Israeli authorities’ efforts to offer a positive view of Israel on the global stage. In 2004, a unit of the Home Front Command was sent to pull people out of the rubble of a hotel in Taba, Egypt, which had collapsed after a terrorist bombing.

A soldier from the Home Front Command readies her chemical warfare suit before taking part in a drill simulating a chemical strike on a building in Azor, south of Tel Aviv. While Israeli emergency services are already capable of responding to any emergency in a matter of minutes, mostly because of years of practice accumulated while dealing with countless terrorist attacks, the possibility of a war on multiple fronts or of unconventional weapons being used require the highest level of preparedness and coordination among the different services. Providing these capabilities, or taking the blame if something goes wrong, is the task of the Home Front Command.

Soldiers in chemical warfare gear simulate putting out a fire from a building hit by a rocket armed with a chemical warhead. With neighbouring Syria deeply engulfed by a civil war in which deadly gas has allegedly been used, there is great concern about the future of its army’s large stockpiles of chemical weapons. The Israeli government has repeatedly stated that should there be any sign of these stockpiles falling into “the wrong hands”, it would take immediate action to protect itself by any means, which could paradoxically fan the flames of the conflict and therefore create additional security risks.

Home Front Command soldiers practice evacuating casualties from the site of a chemical strike. Most of Israel’s population and infrastructure is concentrated in a narrow coastal strip around Tel Aviv, making it extremely vulnerable to unconventional weapons. Knowing this, all Israeli governments have always sought to prevent their enemies from even acquiring such weapons, sending the Air Force to pre-emptively destroying nuclear reactors which could be used to manufacture nuclear weapons both in Iraq and Syria, while at the same time acquiring nuclear weapons themselves to serve as the ultimate deterrent, although this has never been publicly acknowledged.

Home Front Defence minister Gilad Erdan (centre) inspects the level of preparedness of a school in Nazareth Illit. Established in 2011, the Home Front Defence ministry was a controversial addition to a cabinet which already includes a massive Defence ministry and a Public Security ministry. It is currently being debated whether to transfer most of the Home Front Command’s duties to the police and to local authorities, leaving the IDF free to focus on the battlefield. However, some argue that the transfer would expose to increased danger those living in the less developed communities of the country’s periphery, which incidentally are also the ones who get most of the rockets.

Israeli schoolchildren make their way to the bomb shelter as alarm sirens go off, simulating a rocket attack. During the 2006 conflict with Hezbollah, thousands of rockets fell on northern Israel, and the IDF was unable to stop them for more than month. The Air Force succeeded to destroy all of Hezbollah’s long-range rockets on the first days of the conflict, creating the paradoxical situation in which a third of the country was under fire while Tel Avivians went to the beach. This disparity can also be seen with the communities living around Gaza, who experience continuous rocket attacks which are met by a certain degree of indifference by the rest of the country. When some of Hamas’ rockets eventually did reach the central metropolitan area in the last round of fighting, many bitterly joked that finally Tel Aviv’s inhabitants would understand how dangerous the place they live in really is.

Doing classwork in the school’s bomb shelter. As the country’s enemies continue to arm themselves with thousands of newer, heavier and more precise rockets, it seems likely that Israelis will have to live with emergency drills, gas masks and bomb shelters for a long time. Large parts of Israeli society understand this reality as that of a small country surrounded by mortal enemies bent on its destruction, a mindset which also fits with a certain view of Jewish history, rooted in the memories of the Holocaust and of centuries of anti-Semitism, which has played a great role in shaping Israeli policy in matters of security and diplomacy.

With the peace process more or less completely dead, and any regional solution to the conflict with the Arab world nowhere to be seen, the possibility of Israel being somehow destroyed remains a popular argument of conversation both among Jews and Arabs. Living here, it is hard to imagine a different country, one in which children do not have to have a gas mask or know where the nearest shelter is – a “normal country”, maybe the very same “normal country” which the first Zionists had in mind when they embarked on establishing a place where Jews could finally be safe and protected. A bit like in a shelter.